In Goldman Sachs’ 32-page March 2012 report, the word “investment” appears 119 times and “growth” appears 88 times.

“Education” shows up a mere 16 times – which is fine. After all, this is a financial report churned out from the Goldman Sachs “Equity Research” department. They know who this report is targeting and what the bottom line is.

The report spells out to investors that, in short, now is the time for multi-nationals to be investing in Africa or working on their long-term strategy. The continent is flush with commodities ready for export: oil, gold, diamonds, copper, nickel and iron. Growth across the continent is demonstrated by, “14 African countries that grew their GDP by more than 6% pa on average over the last 5 years,” with “improved governmental competence and stability…fewer wars and skirmishes…and some signs of a reversing of the diaspora that saw talent leave.” Goldman Sachs predicts that by 2050 Africa will have the world’s largest workforce, and the United Nations forecasts the African population will expand from one billion people today to three billion by that time.

Again, “education” appears just 16 times, but let’s look at the context in some ways it’s being discussed (all bolded quotes in this post are of our own highlighting):

“But, they have to improve their governance, infrastructure and education (among other factors) to be able to improve their per capita GDP.”

Translation: The countries Goldman Sachs expects to drive African growth potential over the next decade can only do so through improved education (among other factors).

“Solving all of this will take time, patience, education and capital.”

Translation: In order for Africa to take advantage of its agricultural exports, it needs to focus on education.

“The classical development curve for emerging economies sees them exploiting natural resources to grow GDP, bring in foreign currency, educate the population, start low-level manufacturing and work towards developing a virtuous cycle – improved education and higher-value jobs leading to further GDP expansion…For Africa, this virtuous cycle has proved elusive.”

Translation: There isn’t enough focus on education.

“Over the short term talent in-flow can form part of the solution, but over the longer term systemic investment in education is the answer.”

Translation: Education is the answer.

As we can see, education is the necessary foundation that will usher in millions of Africans currently living below the poverty line – defined by living on $1.25 per day – to the middle class. As more students enrol in primary education – 124 million Africans enroled in 2007 versus 82 million in 1999 – this generation should conceivably drive economic growth throughout the continent within the next 20 years.

However, there are a few hitches. The 42 million expansion between ’99 – ’07 is due to the 2000 United Nations Millennium Development Goals initiative, designed to “free people from extreme poverty and multiple deprivations.” Goal #2 was “Achieve universal primary education for boys and girls.” In 2010, the UN realized their initiatives wouldn’t be reached by their target date of 2015, so they reconvened to retool the MDG plan and analyse what needed improvement.

Among the positives and negatives currently listed on the UN MDG website:

“In Tanzania, the enrolment ratio had doubled to 99.6 percent by 2008, compared to 1999 rates (due to abolishing school fees at primary school levels). But the surge in enrolment in developing regions has brought a few set of challenges in providing enough teachers and classrooms.

And Tanzania has embarked on an ambitious programme of education reform, building 54,000 classrooms between 2002 and 2006, as well as hiring 18,000 additional teachers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 30 percent of primary school students drop out before reaching a final grade.”

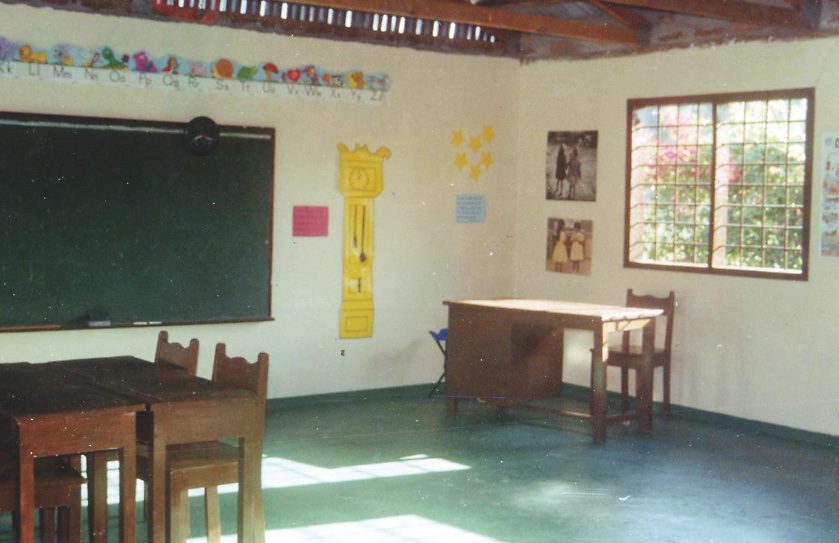

From these stats alone, Tanzania appears on the right track with its education overhaul. But deeper, systemic problems lie just below the surface. Most students attending government school are crammed next to two and three students on a single, rickety bench with one textbook to share amongst themselves, in a classroom with one teacher and more than 60 students. Unfortunately, most government schools fail to provide meals or water, and teacher attendance is a rampant problem. 54,000 classrooms is a feel good stat on paper, but if you don’t have capable, dedicated teachers to instruct lessons – as most schools in Tanzanian don’t – what’s the real bottom line? If a child miraculously makes it to secondary school – an ordeal within itself – the results aren’t pretty: the 2011 National Form Four (10th Grade) Examination results showed that less than ten percent of the candidates scored satisfactory good grades.

So Goldman Sachs is keeping a close eye on the education progress in Africa as they advise investors to pool money into Tanzanian mining, Angolan oil, South African telecommunications, etc. In order to improve education levels – where the farthest reaching effort for reform lies within the UN’s Millennium Development Goals – there needs to be more effective reform than simply “build more classrooms and they will come.” Just because there are more schools, it doesn’t mean the quality of learning inside the classroom is up to par.

Let’s make it clear that the goal shouldn’t be educating students so foreign investors can swoop in to reap the benefits of the locals’ hard work. St Jude’s goal is “fighting poverty through education” – teaching the children so they can go on to improve the lacking infrastructure or open a hospital to battle rampant diseases or choose any of the million opportunities that they’ve worked so hard for, all in the name of lifting Tanzania to a higher level of prosperity and away from the doldrums of extreme poverty.

And yet, let’s return to the Goldman Sachs March Report:

“By 2030, c. 10% of the African population is expected to be in the middle class (our economists define this as those who earn US$6-30k pa), similar to how India is expected to look like in five years, or how China looked ten years ago. Supporting that consumption will be the world’s best demographics; Africa could have the world’s largest workforce by the middle of this century. Who could make money from that? We would argue that US and European consumer companies have plenty of advantages enabling them to take a meaningful slice of that revenue. But if they don’t, others will, with Indian companies making serious inroads, particularly on the East coast. There is very likely a huge amount of unmet demand; it’s not just people wanting to upgrade to better products, the products themselves aren’t currently available.

What are the barriers to entry?”

It’s hard not to be cynical about Goldman Sachs’ intentions, and we’re not the only ones who have noticed. In the Africa Progress Report (APP) 2012, Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations and Nobel laureate, chair of the APP, writes in his foreword:

“There has also been encouraging progress towards some of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Many countries have registered gains in education, child survival and the fights against killer diseases like HIV/AIDS and malaria. None of this is cause for complacency. It cannot be said often enough, that overall progress remains too slow and too uneven; that too many Africans remain caught in downward spirals of poverty, insecurity and marginalisation; that too few people benefit from the continent’s growth trend and rising geo-strategic importance; that too much of Africa’s enormous resource wealth remains in the hands of narrow elites and, increasingly, foreign investors without being turned into tangible benefits for its people.”

Goldman Sachs may be correct in declaring Africa ripe for investment, but they sorely overlook the incredible difficulty in distributing high-quality education, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The School of St Jude is educating its students to become the future leaders of Tanzania and more broadly, Africa. Ultimately, it will be them making the decisions in fifteen, twenty years time as to whether they want to deal with foreign investors. It’s our job now to teach them how to make the ethical, moral and informative decisions they’ll encounter later on in life. We aim to build a cyclical pattern where our students use the knowledge and skills they’ve acquired in the classroom to give back to their community, their region and their country.

This is a fight against poverty, and that is our bottom line.

Replies